Do you think your cell phone is secretly listening to you?

Do you always think you've been bugged by an app on your phone? It's like what we say will push us to the relevant content, chat about what products can be seen on a treasure.

It's not just you who have this question, a developer who suspects that Facebook is always listening to him, so he did some research, and he discovered the computational complexity of Facebook listening to see what he said

Before the blockade began for a few months, I invited a friend over for dinner. He is on a ketogenic diet, a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, mainly meat and cheese. He also told me that white noodles are fine. I don't know what to cook, white noodles are not a good suggestion. The other guest is a vegetarian, so meat, fish, eggs and cheese are not eaten. I muttered dark reviews of the ketogenic diet myself. Finally, we went to a restaurant.

Later that night, as I scrolled through Twitter, an ad for a ketogenic diet bounced out. I've never shown any interest in dieting before, and my brain is running all the time.Are Facebook and Twitter secretly eavesdropping on my conversations?I imagine Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, wearing headphones in the dark and deciding which ads to push me.

Cell phones have ears and laptops have eyes

Well, you can just say: No.Our cell phones don't secretly listen to us.

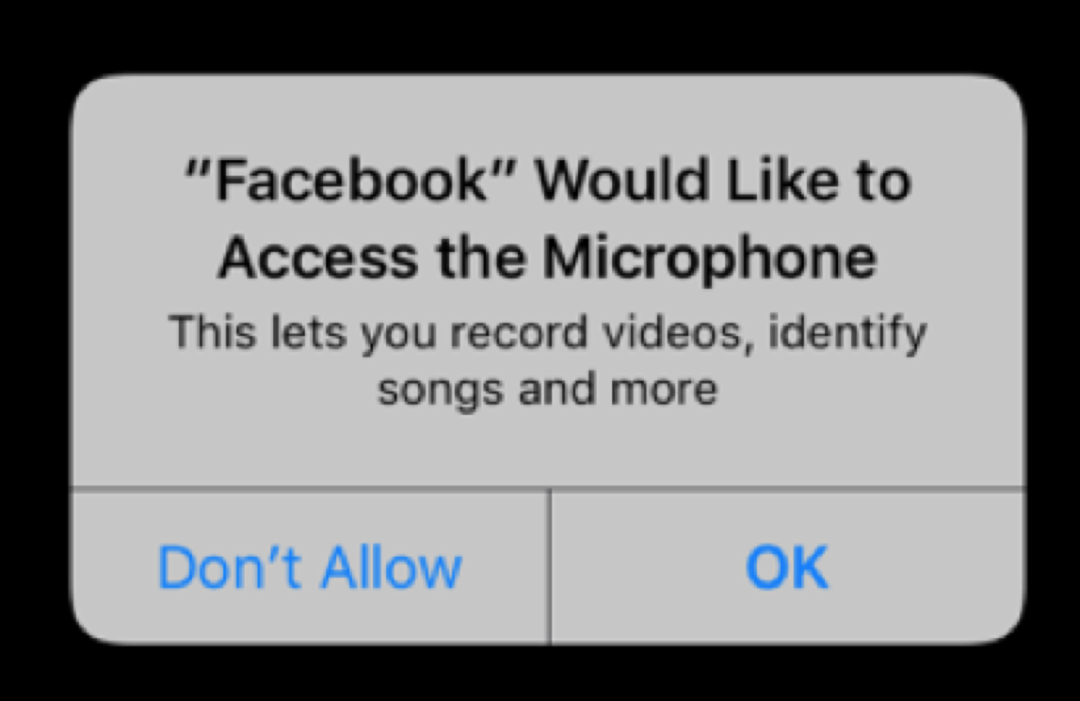

We know there are many ways to show that Twitter and Facebook can't do that. When a developer writes an application for iOS, it runs on an Apple-controlled operating system.Facebook can't access the microphone directly and start recording. The app must be coded from the Apple system.When Facebook requests audio, apples ask users if they want Facebook to access the microphone.

If they want to, the phone sends an audio stream to Facebook. If they don't want to, they don't. Apple's code is a software wall that cannot be accessed if the software is not invited by the user.

When the APP uses a microphone, a toolbar appears at the top of the screen. When I complained about my ketogenic diet friend, there were no toolbars at the screen. But I'm still upset. I check my phone to see which APPS can access my microphone. I knew it wasn't necessary, but I did, and thought it best to check it just in case. It reminds me of a legend: at Harvard, rubbing a statue's shoes brings good luck. Ivy League students are smart and not superstitious. However, the shoes on the left foot are still lit by friction. You know, just in case.

I think maybe Facebook has found a way to bypass apple security checks. But we can verify this again by monitoring Facebook's data from our phones. If Facebook sends audio, we'll see. Even if they find a way to mask traffic, sending this audio requires a lot of bandwidth. The user will find out when the phone charges. And, let's calculate it and we'll see if it's feasible. "Online voice calls take about 24 kbps, and in the United States alone, 20 gigabytes (pb) per day," Antonio García Martinez said in Wired magazine. "Facebook's data center is big, but not that big.

In addition, there are questions about the cost and computational complexity of processing audio, finding keywords, and running ads, and whether it really works.As Martinez puts it, "Human language is full of satire, insinuity, puns, and confusion." "When I talked directly to Siri, it barely worked. Computers are not smart enough to understand what we're saying. Facebook simply can't record our audio all the time. Your phone will get hot and the battery will run out. Physics protects us here even without data protection.

Facebook also denied secretly recording the audio, even though it was the most compelling evidence I've ever found.

Tests showed that Facebook was not listening

I write software, I have friends who work on Facebook, I use APIs and mobile apps to handle things, so I can judge the authenticity of these claims very well, but I still can't help but wonder if they're listening. Can they find a way around physics? This has become my "911 was the work of insiders" (conspiracy theories).

After 9/11 2001, the conspiracy theory emerged that the Bush administration had intercepted the terrorists' action plan in advance, but deliberately failed to intercept it, thus constituting a global military landscape adjustment based on the war on terror. Those who believe in this theory call themselves "truthers" (truth seekers).

I've done two little tests.I put my phone aside, turned on Facebook, and shouted at the air"Oh my God, I really want to go on holiday to the Bahamas. "God, my car insurance is too expensive. It would be nice if someone could find a cheaper offer. "

There's nothing。 I think it's silly.

But the next day, I still looked at every ad with suspicion. Smart journalists who debunk plots are also tempted by them. The New Statesman carried out a similar (equally unscientific) study to me.

Of course, they got similar results:Facebook doesn't listen.

I find that this is not the only rumor that rational people repeat. A planned phase-out is when a new product appears, the old product stops working; software updates are designed to slow down old devices; smartphones cause cancer; hackers secretly spy on you through your laptop camera; and so on.

Sometimes it's just a math problem

The problem is that technology companies don't look reliable. Listening to us through the microphone to run ads is exactly what they do. It's very special. Apple is slowing down the processors of older phones, and there's no denying that it's trying to handle degraded batteries, but we're right to think that phones are getting slower and slower. There are many more bad examples. Christo Wilson, a doctoral student at Northeastern University who has studied several Android apps, said, "Apps automatically take selfies and send them to third parties." Facebook has hired "external contractors to transply audio clips of users of its services" and store "information written but not published by users." There are many examples of this. Our privacy has been violated before.

And sometimes the coincidence of advertising is incredible. I give an example of a ketogenic diet, but everyone has their own story. When PJ Vogt asked for an example on the podcast "Reply All," he received dozens of responses. Time and again, people say it's "creepy." They say something, and the next day it appears in a push.

Professor Dr David Hand explained to the BBC that the reason was mathematics. "If you catch something that's very unlikely to happen and give it enough chance to happen, it's bound to happen." The probability of showing someone the product they've just discussed is surprising. For example, with a one-in-a-million probability, we often use this phrase to describe what is almost impossible to happen. With this probability, every time Facebook posts an ad, 2,500 people just discuss it. If you're thinking about something common, like pasta, and you see a spaghing ad, you probably don't think about it at all. But when it becomes obscure, the idea becomes prominent. This is the Bader-Meinhof phenomenon, created by a man named Terry Mullen, who, after reading about a little-known political faction, the Bader-Meinhof team, re-encountered the word in an unrelated article.

We are deceived, deceived by our illogical brain. Humans are good at identifying patterns。 We're so good at it that we can recognize it even when there's no pattern.

It's no different from magic

However, I do not find these explanations particularly satisfactory. It is no accident that these incredible events happen all the time. What I really want to see is a series of decisions that cause me to see a particular ad at a specific time, explaining how the algorithm syncs with my life experience. Because these ads are not accidental coincidences, they are the result of the recommendation engine using the data points on me.

Why don't Facebook and Google listen to us? Because they don't need it. They know our age, location, interests, websites we visit, and what we've seen. Twitter didn't run a ketogenic diet ad because it overheard me. It did so because I googled what to cook for my friends who adhered to the ketogenic diet, and one of the websites I visited had a tracking pixel that captured this information and advertised it to me. Our digital and "real" lives are so intertwined that it's easy to forget what you searched for on Google and just thought of. Google doesn't need to read what we're thinking, we type in our thoughts. Facebook doesn't listen to us, it listens to what we think.

Arthur C. Clarke famously said, "Any technology that is advanced enough is no different from magic." "The technology is already advanced enough. Even 10 years ago, Facebook could collect 500 tbsb of data a day. With so much data, it can make seemingly magical connections.

This is the world of Facebook, and we live in it

These explanations are no more satisfying than finding out how magicians perform magic. Mirrors, magnets and trap doors are so ordinary that we can't believe they're behind what's visible to the naked eye on stage. We've all played cards, so we think we know what's possible. We forget that magicians have practiced their cards for thousands of hours, and that they have a different card in their hands than in ours. Similarly, technology companies operate in a very different way from ours. We've heard that they violate privacy laws, but usually in subtle ways. Who can really explain what invasions of privacy are included in Facebook's record-breaking $5 billion fine? (In fact, all the fines since then have been for not know anything.) )

This low-trust environment is an ideal breeding ground for conspiracy theories. Professor Karen Douglas, of the University of Kent, said: "Research shows that people are attracted to conspiracy theories when they feel powerless. "Compared to Facebook, there's nothing we can do. We found something, we knew their secrets, and the idea was that we could regain some power. Psychologist Dr Anthony Lantian wrote: "People who believe in conspiracy theories feel 'special' and they feel more knowledgeable than others. "

In Democracy and Truth, Sophia Rosenfeld argues that conspiracy theories are prevalent in societies where there is a huge gap between the ruler and the underdial ruler. Technology companies may not be able to manage us (not literally, nor now), but they have the knowledge and resources we don't have. There is a growing gap between what they can do and how we understand how they do it. In Workshop and The World, Robert Crease says that this "creates a rift between those who cannot understand this particular language and those who understand it, making it easy for the former to distrust the latter." "

We often think of paranoia as conspiracy theories. But a more reasonable explanation is that these ideas stem from powerlessness. Jeff Atwood writes that even software developers have to "work for Wang." Everyone is in the hands of larger, higher-quality companies in the food chain.

Compared with the tech giants with millions of users, we are nothing more than tiny, tiny and powerless digital ant colonies. It's nice to have someone listening to me. I'm important, I have an impact! Even if it's just to sell me the popular low-carbohydrate diet.

I don't want Facebook to listen in on me, but what's even more frustrating is that we're not important enough for them to try to listen.

Java Development Microserver Purchase Mall Battle - Episode 357Code courseware attached】

Java MicroServer Real Grain Mall -296 Episodes (Code Courseware)

Spring Boot develops small, beautiful personal blog with courseware and source code

2020 WeChat Small Program Full Stack Project's Friends (With Courseware and Source Code)

Every one of your points is watching, and I take it seriously as a favorite

Go to "Discovery" - "Take a look" browse "Friends are watching"